The problem with the current layered model of the Internet

The conventional view serves to protect us from the painful job of

thinking.

-- John Kenneth Galbraith

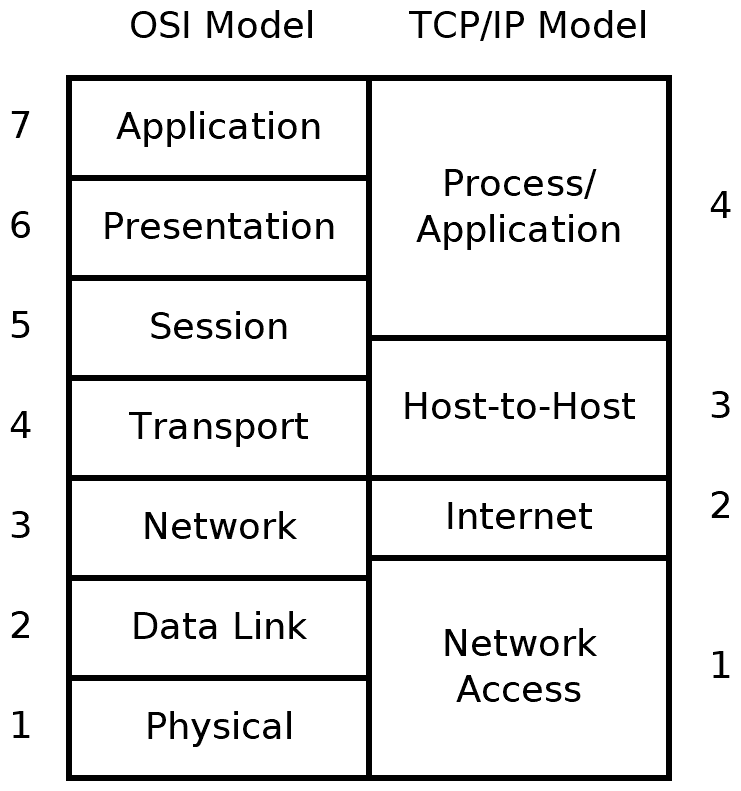

Every engineering class that deals with networks explains the 7-layer OSI model and the 5-layer TCP model.

Both models have common origins in the International Networking Working Group (INWG), and therefore share many similarities. The TCP/IP model evolved from the implementation of the early ARPANET in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s. The Open Systems Interconnect (OSI) model was the result of a standardization effort in the International Standards Organization (ISO), which ran well into the nineties. The OSI model had a number of useful abstractions: services, interfaces and protocols, where the TCP/IP model was more tightly coupled to the Internet Protocol (IP).

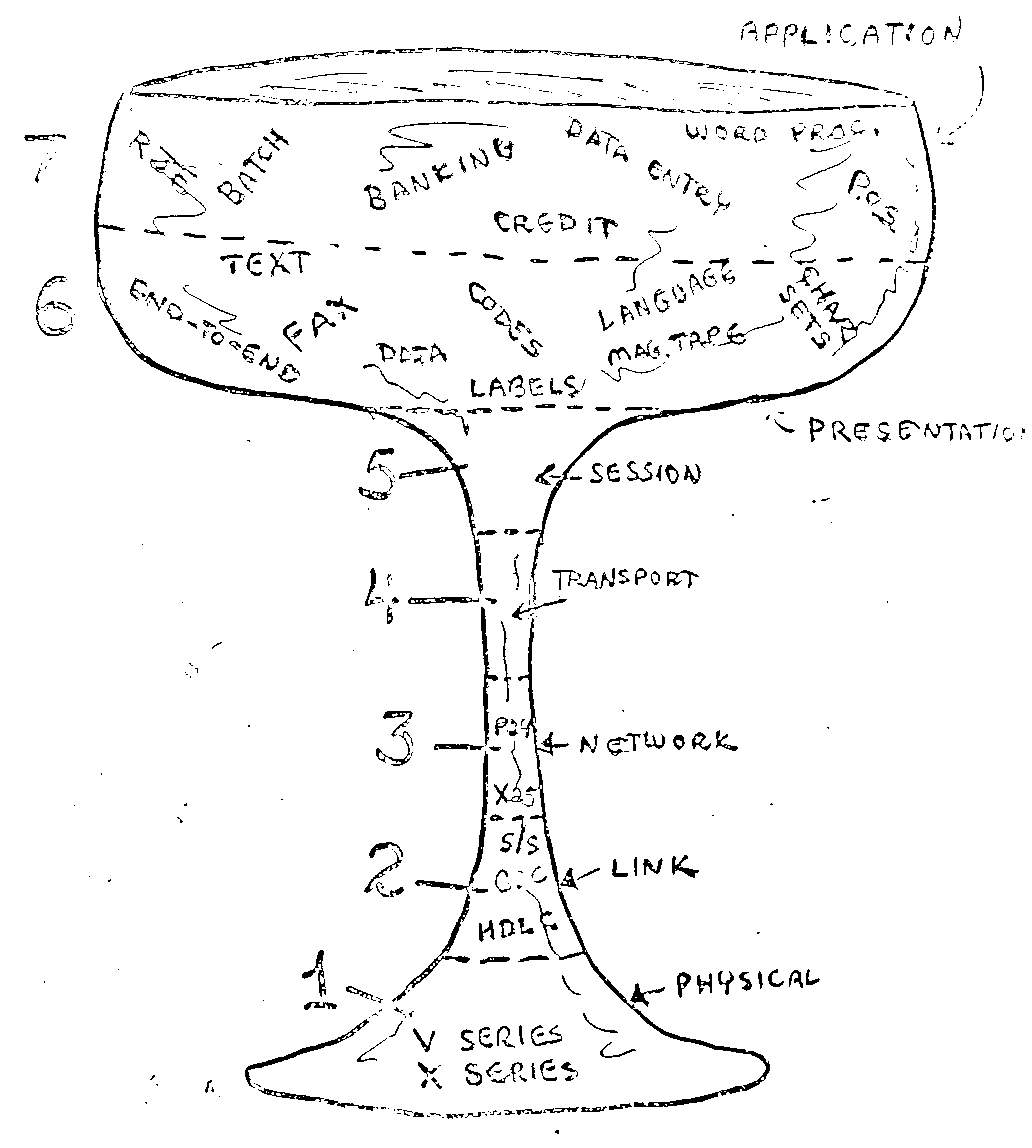

A birds-eye view of the OSI model

Open Systems Interconnect (OSI) defines 7 layers, each providing an abstraction for a certain function, or service that a networked application may need. The figure above shows probably the first draft of the OSI model.

From top to bottom, the layers provide (roughly) the following services.

The application layer implements the details of the application protocol (such as HTTP), which specifies the operations and data that the application understands (requesting a web page).

The presentation layer provides independence of data representation, and may also perform encryption.

The session layer sets up and manages sessions (think of a session as a conversation or dialogue) between the applications.

The transport layer handles individual chunks of data (think of them as words in the conversation), and can ensure that there is end-to-end reliability (no words or phrases get lost).

The network layer forwards the packets across the network, it provides such things as addressing and congestion control.

The datalink layer encodes data into bits and moves them between hosts. It handles errors in the physical layer. It has two sub-layers: Media access control layer (MAC), which says when hosts can transmit on the medium, and logical link control (LLC) that deals with error handling and control of transmission rates.

Finally, the physical layer is responsible for translating the bits into a signal (e.g. laser pulses in a fibre) that is carried between endpoints.

The benefit of the OSI model is that each of these layers has a service description, and an interface to access this service. The details of the protocols inside the layer were of less importance, as long as they got the job – defined by the service description – done.

This functional layering provides a logical order for the steps that data passes through between applications. Indeed, existing (packet) networks go through these steps in roughly this order.

A birds-eye view of the TCP/IP model

The TCP/IP model came directly from the implementation of TCP/IP, so instead of each layer corresponding to a service, each layer directly corresponded to a (set of) protocol(s). IP was the unifying protocol, not caring what was below at layer 1. The HOST-HOST protocols offered a connection-oriented service (TCP) or a connectionless service (UDP) to the application. The TCP/IP model was retroactively made more “OSI-like”, turning into the 5-layer model, which views the top 3 layers of OSI as an “application layer”.

Some issues with these models

When looking at current networking solutions in more depth, things are not as simple as these 5⁄7 layers seem to indicate.

The order of the layers is not fixed.

Consider, for instance, Virtual Private Network (VPN) technologies and SSH tunnels. We are all familiar enough with this kind of technologies to take them for granted. But a VPN, such as openVPN, creates a new network on top of IP. In bridging mode this is a Layer 2 (Ethernet) network over TAP interfaces, in routing mode this is a Layer 3 (IP) network over TUN interfaces. In both cases they are supported by a Layer 4 connection (using, for instance Transport Layer Security) to the VPN server that provides the network access. Technologies such as VPNs and various so-called tunnels seriously jumble around the layers in this layered model.

How many layers are there exactly?

Multi-Protocol Label switching (MPLS), a technology that allows operators to establish and manage circuit-like paths in IP networks, typically sits in between Layer 2 and IP and is categorized as a Layer 2.5 technology. So are there 8 layers? Why not revise the model and number them 1-8 then?

QUIC is a protocol that performs transport-layer functions such as retransmission, flow control and congestion control, but works around the initial performance bottleneck after starting a TCP connection (3-way handsake, slow start) and some other optimizations dealing with re-establishing connections for which security keys are known. But QUIC runs on top of UDP. If UDP is Layer 4, then what layer is QUIC?

One could argue that UDP is an incomplete Layer 4 protocol and QUIC adds its missing Layer 4 functionalities. Fair enough, but then what is the minimum functionality for a complete Layer 4 protocol? And what is a minimum functionality for a Layer 3 protocol? What have IP, ICMP and IGMP in common that makes them Layer 3 beyond the arbitrary concensus that they should be available on a brick of future e-waste that is sold as a “router”?

Which protocol fits in which layer is not clear-cut.

There are a whole slew of protocols that are situated in Layer 3: ICMP, SNMP… They don’t really need the features that Layer 4 provides (retransmission, …). But again, they run on top of Layer 3 (IP). They get assigned a protocol number in the IP field, instead of a port number in the UDP header. But doesn’t a Layer 3 protocol number indicate a Layer 4 protocol? Apparently only in some cases, but not in others.

The Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) performs (inter-domain) routing. Routing is a function that is usually associated with Layer 3. But BGP runs on top of TCP, which is Layer 4, so is it in the application layer? There is no real concensus of what layer BGP is in, some say Layer 3, some (probably most) say Layer 4, because it is using TCP, and some say it’s application layer. But the concensus does seem to be that the BGP conundrum doesn’t matter. BGP works, and the OSI and TCP/IP models are just theoretical models, not rules that are set in stone.

Are these issues really a problem?

Well, in my opinion: yes! These models are pure rubber science. They have no predictive value, don’t fit with observations of the real-world Internet most of us use every day, and are about as arbitrary as a seven-course tasting menu of home-grown vegetables. Their only uses are as technobabble for network engineers and as tools for university professors to gauge their students’ ability to retain a moderate amount of stratified dribble.

If there is no universally valid theoretical model, if we have no clear definitions of the fundamental concepts and no clearly defined set of rules that unequivocally lay out what the necessary and sufficient conditions for networking are, then we are all just engineering in the dark, progress in developing computer networks condemned to a sisyphean effort of perpetual incremental fixes, its fate to remain a craft that builds on tradition, cobbling together an ever-growing bungle of technologies and protocols that stretch the limits of manageability.

Not yet convinced? Read an even more in-depth explanation on our blog, about the seperation of concerns design principle and layer violations and about seperation of mechanism & policy and ossification.